Remember the Monarchs

Rachel Carson’s Last Summer at Southport

By Edgar Allen Beem

Photos by Michele Stapleton

“When the tide is high on a rocky shore, when its brimming fullness creeps up almost to the bayberry and the junipers where they come down from the land, one might easily suppose that nothing at all lived in or on or under these waters of the sea’s edge.”

So wrote Rachel Carson, perhaps the greatest environmentalist of the 20thcentury, in The Edge of the Sea. Carson was describing the littoral landscape just below her small summer cottage on Southport Island west of Boothbay Harbor. The low, one-story silvery gray home with its seaside deck sits like a wooden gull above the shore of the Sheepscot River between Dogfish Head and Hendricks Head Light.

The Carson cottage is an accurate reflection of the woman herself. A modest dwelling simply furnished with pine paneling, rattan chairs, books, nautical charts, sunlight, and sea air, her summer home is an artifact of the 1960s, intimate and authentic in ways that very few Maine summer cottages are anymore. The cottage defers to the site, hiding atop the ledges in the trees, not calling attention to itself.

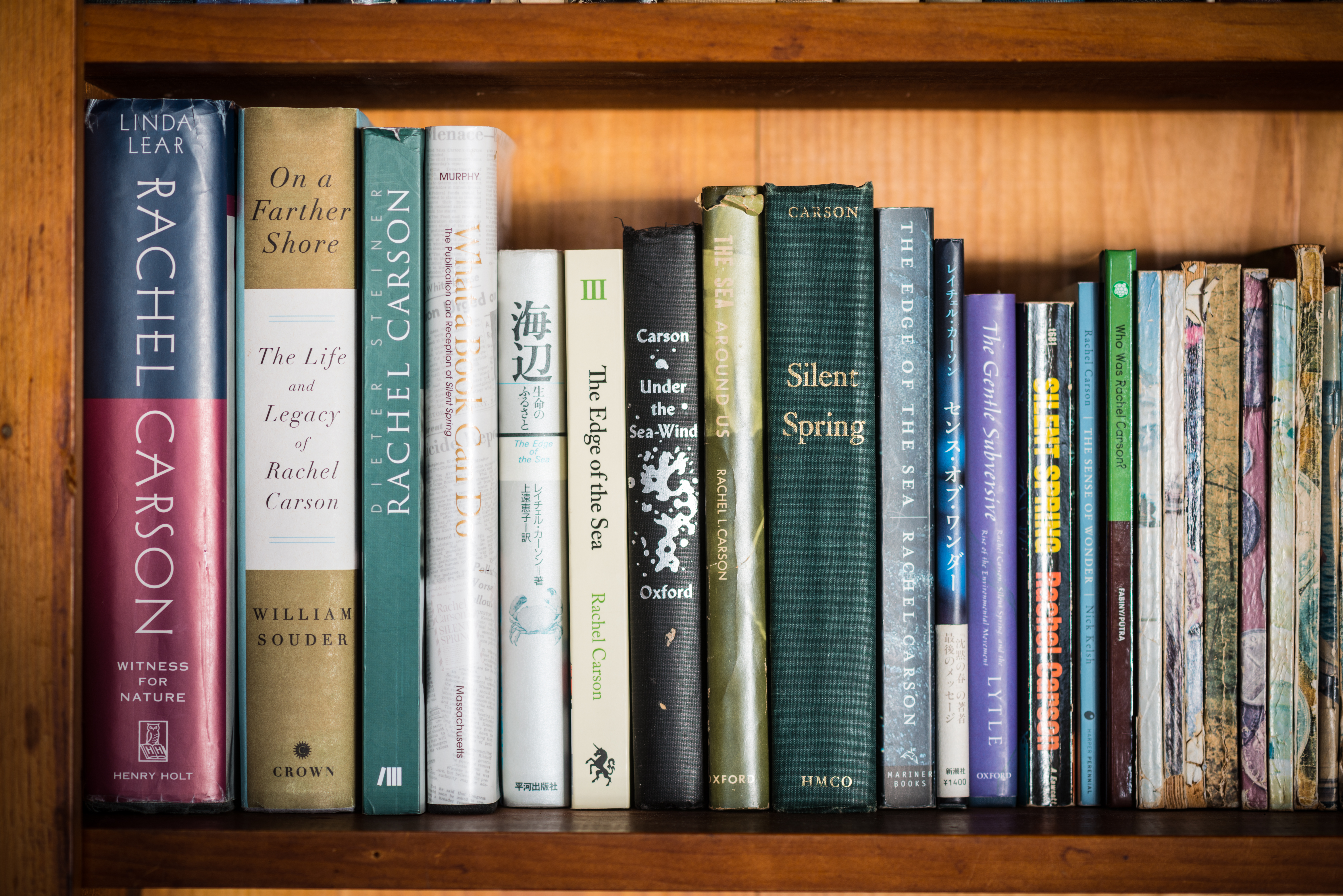

Just so, Rachel Carson was a modest woman who lived a quiet life beside the sea, yet her work had a global impact. Carson (1907-1964) was a federal employee much of her working life, but her sea trilogy—Under the Sea-Wind (1941), The Sea Around Us (1951), and The Edge of the Sea (1955), established her as one of America’s leading nature writers. Silent Spring (1962), Carson’s bombshell documentation of chemicals in the environment, led directly to the banning of DDT and indirectly to the founding the Environmental Protection Agency.

* * *

Rachel Carson first came to Maine in 1946, renting a cottage for a month near Boothbay Harbor with her mother. In 1953, she built the cottage on Southport Island where she spent the happiest years of her life.

“Maine was her haven. It was her laboratory and it gave her the solitude to write,” says Martha Freeman, who edited the voluminous letters between Carson and her Freeman’s grandmother, Dorothy Freeman, and published them as Always, Rachel (1995). “Without Maine in her life, she couldn’t have done Silent Spring. Maine was her refuge. It re-energized her. It was her relation with nature. And she had my grandmother.”

Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman met when Carson moved to Maine and became the best of friends. Carson was an unmarried 46-year-old woman and Freeman a 55-year-old wife, mother, and grandmother when they met. In Maine, they explored the shores and woods together, sharing a love of nature and a companionship in the outdoors. Freeman became Carson’s best reader, confidant, and kindred soul. Carson was the writer Freeman had hoped to become. When they returned home—Carson to Silver Springs, Maryland and Freeman to West Bridgewater, Massachusetts, they wrote so often that Martha Freeman inherited an entire maroon plaid suitcase full of their correspondence, some 750 letters in all.

Though she became a major figure in the public life of America with the publication of Silent Spring, Carson was a very private person. One of the amazing things about her was how much she was able to accomplish despite the weight of family responsibilities that fell to her.

As an unmarried daughter, Carson became the caretaker for her aged mother. When her older sister died, leaving two young daughters, she took on that responsibility as well. When one of her nieces died at 31, leaving a five-year-old son, Carson dutifully adopted her grandnephew Roger Christie as her own son. All this while working full-time for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and writing her books.

* * *

When Silent Spring appeared in 1962, Carson found herself taking on not only the chemical industry, but government regulators and the media as well. For questioning the amount of toxic chemicals being pumped into the atmosphere, she was attacked as a spinster, a pseudo-scientist and a mystic. Time magazine, to its everlasting shame, was especially hard on Carson, calling Silent Spring “unfair, one-sided, hysterically overemphatic” and “nonsense.” The unnamed author of the Time review claimed DDT was perfectly safe, citing a government scientist who claimed to have fed 200 times the “safe” level of DDT to convicts for months with “no ill effects.”

The fact that Carson was able to prevail over industry, regulators, and media critics, says her son Roger Christie, who inherited the Southport cottage, was a function of the kind of person Rachel Carson was.

“She was a pretty compelling person,” says Christie. “She was good and she was thorough. She took great pains to document everything she was doing. She would just lock herself away and work. I’d ask her to do something and she’d say, ‘No, I’m in the study footnoting.’ The fact that she did it all while she was dying is even more remarkable. She wanted someone else to do it, but she couldn’t find anyone, so she did it herself.”

Carson struggled with cancer and a heart condition the last few years of her life, though male doctors never gave her the full diagnosis, as women were felt to be too fragile to handle the truth.

Then, as now, an earnest person in possession of a scientific truth could be subjected to partisan attacks and charges of fake news, but Rachel Carson only needed an audience of three powerful men to get her Silent Spring message out to the world. New Yorker editor William Shawn serialized the book, CBS Reports news anchor Eric Sevaried presented Carson to an audience of 15 million viewers, and President John F. Kennedy saw to it that Carson’s findings in Silent Springwere included in “The Uses of Pesticides,” a report of the President’s Science Advisory Committee.

“She was the apex of something going on all around the country,” says Martha Freeman, that something being the dawning of an environmental consciousness, the realization that human beings are part of the natural world, not separate and apart from it. “She was laser-focused, an efficient organizer, an excellent researcher, a great writer. And Kennedy wanted the facts. Government officials believed one of their constituencies was the facts, reality. That doesn’t seem to be true today.”

* * *

After the watershed Silent Spring year, Rachel Carson sought refuge in Maine the following summer, her last summer on Southport. She and young Roger arrived on June 25, 1963, and Roger, 11, was quickly sent off to camp at Chewonki for the month of July.

In mid-summer, Rachel Carson sent a note to Dorothy Freeman asking, “Would you help me search for a fairy cave on an August moon and low, low tide? I would love to try once more, for the memories are precious.”

The tide pools, stone beaches, and sea caves along the rocky Southport shore were Carson’s favorite marine landscapes. She loved nothing better than spending her time exploring the marine life at the edge of the sea. But when he returned from summer camp, Roger Christie discovered that Carson had been unable to climb down over the steep ledges to the rocks below the cottage.

“I knew she was ill,” recalls Christie, “but I didn’t know she was dying.”

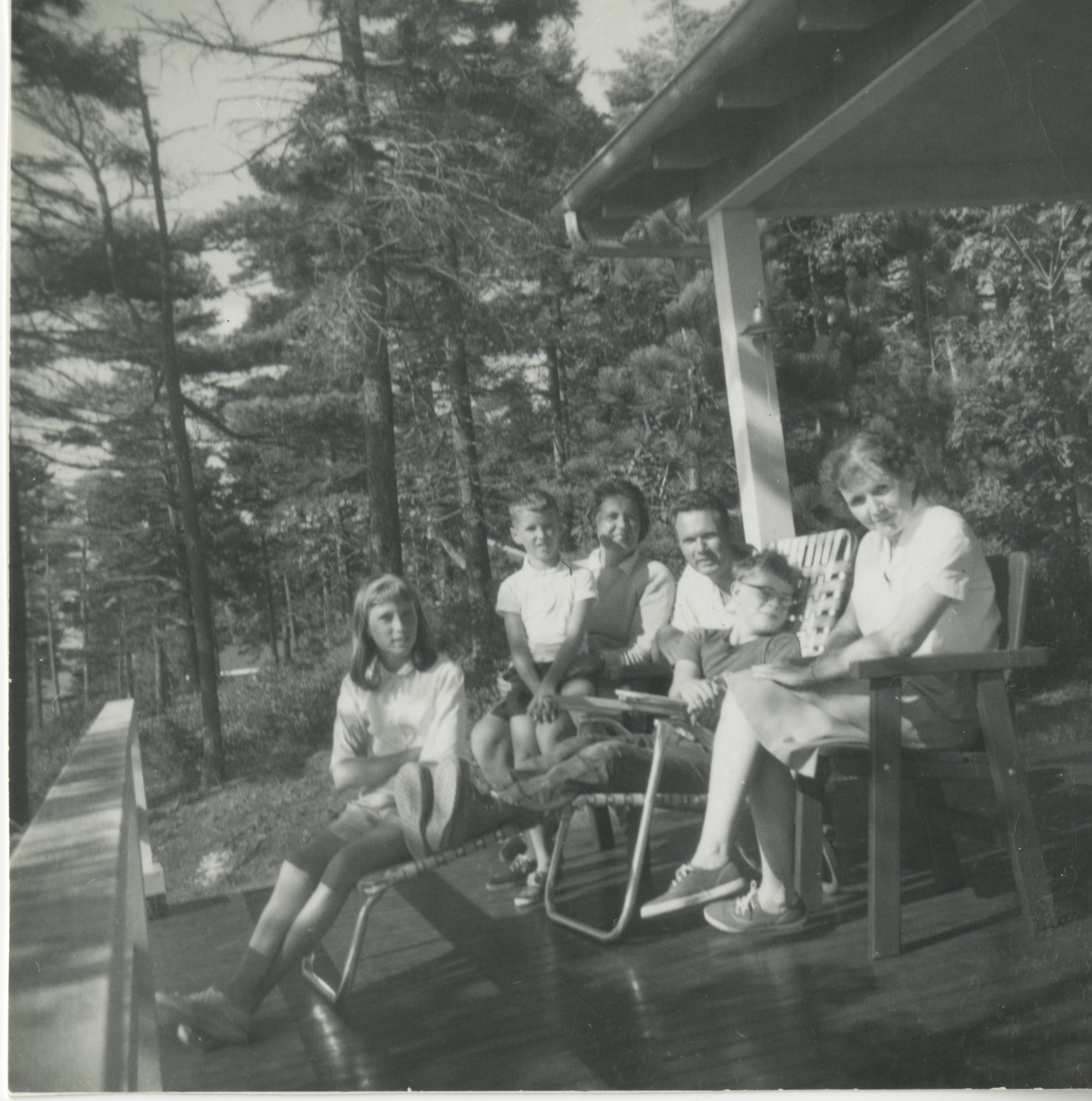

Carson’s last tide pool expedition took place remotely in September 1963 when Christie, his friend Martha Freeman, and Martha’s parents brought specimens up to the cottage for Carson to examine under her microscope and then, at her insistence, dutifully returned them to the natural world.

“She taught us to have respect for other forms of life on the planet and to be good stewards of the Earth,” says Christie of his mother’s legacy.

On September 9, Carson’s cat Moppet died. The following morning she and Dorothy Freeman went to the Newagen Inn where they sat together on a bench above the shore watching the sea and sky and listening to the wind in the spruces, the surf on the rocks, and the gulls crying in the distance.

The highlight of that outing was the spectacle of a drift of hundreds of Monarch butterflies, riding the breeze from milkweed to milkweed before lifting off for Mexico. Already in a funereal mood, the two women speculated that these lovely orange and black butterflies would not live to return to Southport.

“But it occurred to me this afternoon,” wrote Carson to Freeman later that same day, “remembering that it has been a happy spectacle, that we had felt no sadness when we spoke of the fact that there would be no return. And rightly—for when any living thing has come to the end of its life cycle we accept that end as natural … when that intangible cycle has run its course it is a natural and not unhappy thing that a life comes to an end … That is what those brightly fluttering bits of life taught me this morning. I found a deep happiness in it—so, I hope, may you. Thank you for this morning.”

Carson died the following spring, April 14, 1964, in a Cleveland hospital without ever returning to Maine. Christie, Dorothy Freeman and the people who loved her scattered some of her ashes along the shore below the Newagen Inn.

A pair of white Adirondack chairs mark the spot, a comfortable perch from which to contemplate the natural world. On a quiet morning when no gulls call and lobster boats are too far off to be heard, silent clouds propelled by invisible winds cast shadows on the eternal rock and the gray-green brine from which we all came and to which we all return.

Just below the chairs is a bronze plaque mounted on a split boulder, marking where Rachel Carson’s earthly remains were returned to the sea.

“But most all,” reads the inscription, “I shall remember the Monarchs.”

Edgar Allen Beem is a freelance writer living in Brunswick. He has written about the cultural life of Maine since 1978 in such publications as Maine Times, Down East, Yankee, Boston Globe Magazine, The Forecaster, Maine Arts Journal and Island Journal.